LAKE TAHOE, Calif./Nev. – Temperature can mean the difference between four inches of rain and four feet of snow. That’s something the Tahoe region, and much of the west, has experienced this winter, evidenced by above normal precipitation, yet being plagued with what hydrologists call a “snow drought.”

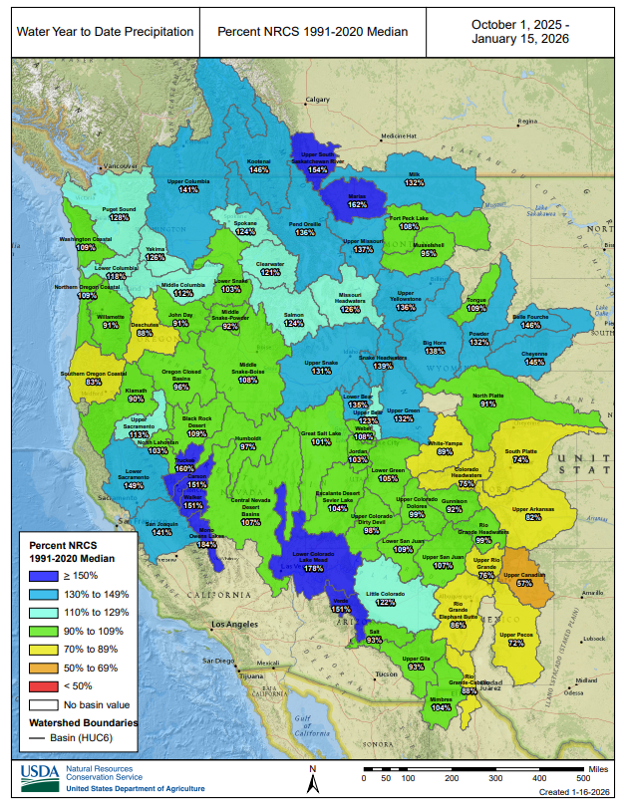

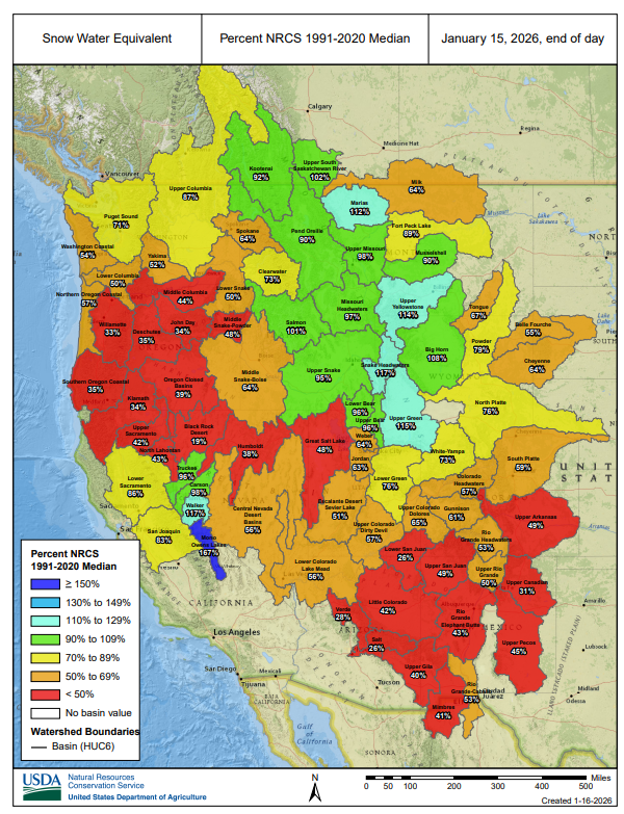

Snow droughts come in two forms, dry and what the region is currently experiencing—wet. The Tahoe Basin has received 155% precipitation since Oct. 1, yet only a 95% of median snowpack.

Had the November precipitation brought four feet of snow, rather than the four inches of rain, those two values would likely be closer together with a more generous snowpack, “which would have put resorts in great shape for Thanksgiving,” Natural Resources Conservation Service hydrologist, Jeff Anderson, said, “instead of scrambling to open terrain after the Christmas storm.”

The holiday storms over Christmas and New Years brought a combined 90-plus inches of snow according to UC Berkeley Central Sierra Snow Lab, bringing the snowfall to around median levels and on track for the year, at least for now.

Much of the west hasn’t been so fortunate with the disparity between precipitation and snow continuing.

With all the talk of “snow droughts”, it may come as a surprise that California is completely drought free for the first time since 2000 (though it came close in 2005 and 2011) according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. It’s a nod to how much precipitation the west coast has received as well as other measures such as streamflow, reservoir levels, temperature and evaporative demand, soil moisture and vegetation health.

Meteorologist Heather Waldman says, “Drought is hard to define and the Drought Monitor is an imperfect tool for California’s climate, but the current water year is off to a wet start no matter how you look at it.”

The climate that defines California now, could shortly become a very different story. The California Department of Water Resources (DWR) notes in its Dec. 30 report that although drought and flood have always marked the California climate, “extreme whiplash between wet and dry is becoming more pronounced, not just year to year but often within the same season or month.”

The Sierra snowpack supplies about 30% of California’s water needs, which is why it is referred to as the state’s frozen reservoir. According to DWR, the water supply this year will depend on a continued cadence of storms in winter and early spring.

With the largest snow-producing months in the Sierra Nevada, on average, being January, February, and March, much of this winter’s story is still untold.

Should a snow drought continue, what could that mean for the Tahoe region?

Anderson explains that since so much of the Tahoe Basin is the lake surface itself, both rain and snow immediately help fill the lake, so long as there is room to store water.

Lake Tahoe currently has 1.5 feet of storage available until it reaches its legal limit. Once the limit is met, water managers are required to release water.

Each year water managers try to fill Lake Tahoe. In a good snow year, snowmelt in spring and summer replaces the water being released, keeping the lake’s water elevation high. During a wet snow drought, however, too much rain could disrupt this scenario, possibly leading to a mismatch between water availability and water demand.

If the lake fills mid-winter, water must be released before there is downstream demand. This is compounded in spring as there is less snow to melt and inflow is outpaced by demand, sooner leading to lower lake levels.

Skiers, snowboarders and resorts are likely the ones feeling the immediate impact of the snow drought this winter, but if it continues, it will be felt in different ways throughout the year.

“One of the main issues with warm snow droughts is felt the following summer as forests melt out sooner than they would have if there had been more snow,” Anderson explains. “This would lead to a longer snow free season, and increase wildfire risk.”

Both the DWR and NRCS provide monthly updates on the snowpack and water forecast each month through spring.

The Tribune will continue to provide updates as the winter unfolds.